| |

| Volume 14, Number 8 | May 28, 2024 |

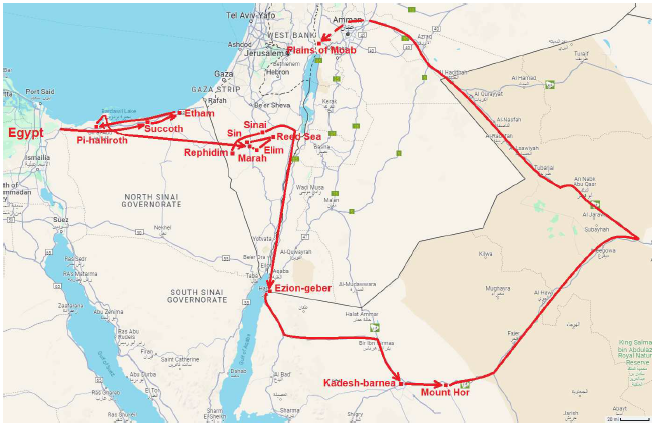

The official itinerary of the Exodus journey from Egypt to Canaan found in Numbers 33:1–49 lists a total of 41 encampments along the way. So far in this series, 12 of these 41 encampments have been identified: Succoth, Etham, Pi-hahiroth, Marah, Elim, Reed Sea, Wilderness of Sin, Rephidim, Wilderness of Sinai, Ezion-Geber, Kadesh-barnea, and Mount Hor. This issue, the Plains of Moab encampment is identified. It is number 41, the last encampment of the list. At this final encampment, a chapter in the history of the Israelite nation would close, and a new chapter would begin. Moses would die at 120 years of age, and Joshua would lead the nation across the Jordan River into Canaan, beginning the Eviction/Conquest.

I am skipping ahead to this final encampment this issue deliberately to enable the overall route of the Exodus from Egypt to Canaan to be sketched on a map at this point.

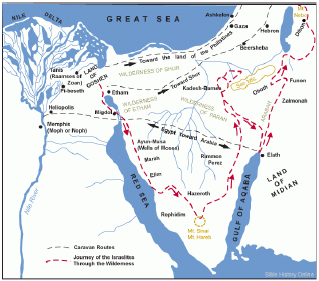

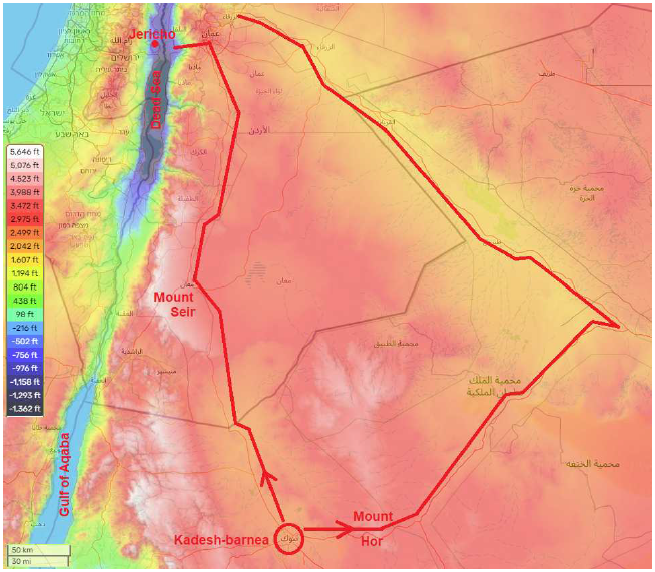

The first encampment of the Exodus (number 1) was at Succoth. The discovery of the location of Succoth, 28 years ago, was very exciting.[1] It solved the longstanding mystery of the path the Israelites had taken out of Egypt. It showed that the traditional choice—the route south (Figure 1)—was mistaken. It showed that the North Sinai road was the route the Israelites had actually taken.

|

The traditional choice of path the Israelites took on the final leg of their journey, from Kadesh-barnea to the plains of Moab on the threshold of Canaan, is similarly mistaken. Discovering the correct path, shared this issue, nearly three decades later, has been similarly exciting.

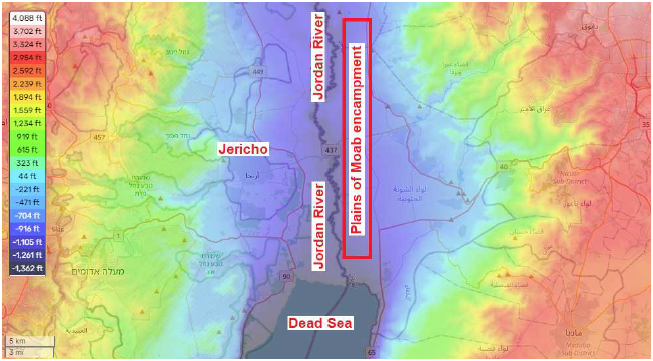

Pinpointing the location of the Plains of Moab encampment is not at all difficult (Figure 2). This results from the fact that the biblical record regarding it is clear and easily understood.

And they journeyed from the mountains of Abarim, and camped in the plains of Moab by the Jordan opposite Jericho. (Numbers 33:48)

|

The location of the Jordan River has been known for a very long time. This is the river connecting the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea. The Plains of Moab encampment was beside this river.

The location of Jericho has also been known for a very long time. It lies just a few miles north of the Dead Sea, on the west side of the Jordan River. This makes it clear that the Israelite encampment was situated across the river from Jericho, on the east side of the Jordan River.

Now, the plains comprising the east bank of the Jordan River are not very wide—just two or three miles in most places. They end abruptly in steep ascents and cliffs up into the mountains to the east. They are widest just north of the Dead Sea opposite Jericho, possibly explaining why this particular location along the east bank of the Jordan River was chosen as the camping spot.

We have learned, in this series, that the typical size of Israelite encampments was 24 or 25 square miles.[2] This implies an oblong encampment in this case. If the encampment was rectangular and three miles wide, then it would need to have been roughly eight miles long, or if it was rectangular and two miles wide, it would need to have been roughly 12 miles long. This unusually extended encampment shape seems to be reflected in the biblical record of it.

And they camped by the Jordan, from Beth-jeshimoth as far as Abel-shittim in the plains of Moab. (Numbers 33:49)I do not yet know where the two cities of Beth-jeshimoth and Abel-shittim were located in the plains of Moab, but their locations are not needed to glean the idea that the final encampment seems to have been stretched out some significant distance along the river.

Locating the Plains of Moab encampment was easy. In fact, I found it to be the easiest to locate of the 41 encampments of the Exodus. In contrast, figuring out how they got there, from Tabuk/Kadesh-barnea, was a significant mental exercise.

It turns out that they got there by making a very wide sweep out into the desert wilderness to the east (Figure 3). I do not think there is anything intrinsically difficult about this discovery. In fact, in hindsight, it seems somewhat obvious. But just because a thing happens to be true doesn't make it automatically easy to believe, especially when it differs so radically from traditional expectations as in this instance. Once one has reconciled to this route, the biblical narrative of the journey from Kadesh-barnea to the plains of Moab begins to make a lot more sense than it ever previously did.

|

If you want to travel from Tabuk/Kadesh-barnea to the plains of Moab today, you have only two choices. Starting from Tabuk, you can take the road to the north, or you can take the road to the east. These same two choices seem to have pertained back at the time of the Exodus.

Well, I suppose one might imagine a third choice. The Israelites would have been traveling on foot, so it is conceivable that they might have hiked cross country. They had done this once before, on the way to Marah, following the Reed Sea crossing.[3] But two factors argue against this option in this instance.

First is the distance involved. It had been a three-and-a-half day journey from the Reed Sea to Marah, and it had ended in near crisis, with no water to be found for the first three days, and the water at Marah too saline to drink when they arrived there. If the cross-country hike from the Reed Sea to Marah had been bad, the cross-country hike from Kadesh-barnea to the plains of Moab could be expected to be much worse. The distance in this latter case is more than eight days (245 miles) as the crow flies.

Second is the nature of the journey. When the Israelites had traveled from the Reed Sea to Marah, they were newly escaped slaves. They had left their homes back in Egypt. In contrast, when they traveled from Kadesh-barnea to the plains of Moab, they were moving their homes to the Promised Land where they would make their new homes—they were taking with them nearly everything which they had accumulated after nearly 40 years of residence at Kadesh-barnea. A nature trek of three and a half days as a camping expedition carrying minimal possessions is one thing. A nature trek of over eight days as a means of moving one's home is an entirely different story. The Israelites would need to have used the road, where the going would be relatively easy and where access to water would be reasonably assured, on their journey from Kadesh-barnea to the plains of Moab.

There are only two roads from Tabuk/Kadesh-barnea leading ultimately to the desired destination (Figure 3). The shortest route runs northward from Tabuk, first within the valley in which Tabuk/Kadesh-barnea is located, and then along the base of mountains on an elevated plain. A significantly longer route runs eastward from Tabuk, crosses Mount Hor, then heads northeast to connect with a valley, and then turns northwest to follow the valley to the mountains bordering the Jordan River.

If you have followed this series to the present time, then you know that the Israelites left Kadesh-barnea by the long route heading east. You know this because you now know that their first encampment out from Kadesh-barnea was at Mount Hor, and the location of Mount Hor, a day's journey east of Kadesh-barnea on Route 15, has been unambiguously identified as part of this series.[4]

The short route would have been preferable, not only because it was shorter, but also because it was more elevated—at higher altitude—and thus cooler.

The long route through the desert wilderness to the east was much longer. Using Google maps, I find an additional 240 miles compared to the shorter route. At 30 miles per day—normal for the Israelites on foot, as we have previously seen in this series[5]—this would add another eight days to the journey.

The short route would have taken them through Edom, where the sons of Esau lived, which lay immediately to the north of Kadesh-barnea:

Now turn north, and command the people saying, "You will pass through the territory of your brothers the sons of Esau who live in Seir; and they will be afraid of you. So be very careful; do not provoke them, for I will not give you any of their land, even as little as a footstep because I have given Mount Seir to Esau as a possession." (Deuteronomy 2:3–5)

From Kadesh Moses then sent messengers to the king of Edom: "… now behold, we are at Kadesh, a town on the edge of your territory. Please let us pass through your land." (Numbers 20:14a, 16b–17a)

The fact that the alternative route was so much less desirable explains why Moses tried so hard to get permission from the king of Edom to use the road through Edom.

Edom, however, said to him, "You shall not pass through us, lest I come out with the sword against you." Again, the sons of Israel said to him, "We shall go up by the highway, and if I and my livestock do drink any of your water, then I will pay its price. Let me only pass through on my feet, nothing else." But he said, "You shall not pass through." And Edom came out against him with a heavy force, and with a strong hand. Thus Edom refused to allow Israel to pass through his territory; so Israel turned away from him. (Numbers 20:18–21)

And this fact also explains why the people, whom we might expect to be singing and praising God on their way at long last to the Promised Land, are recorded to have fallen into grumbling against God instead:

Then they set out from Mount Hor by way of the Red Sea, to go around the land of Edom; and the people became impatient because of the journey. And the people spoke against God and Moses, "Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we loathe this miserable food." (Numbers 21:4–5)The eastern route entailed a long, hot, unpleasant desert journey to have to be made on foot carrying one's earthly possessions. As they toiled along, day after day, the gruelling ordeal soon displaced even the promise of new dwellings in their bountiful ancestral homeland awaiting them at the end of the road.

Figure 4 shows the overall route of the Exodus, from Egypt to Canaan, resulting from this series to this point. This route consistently provides a geographical context in harmony with the biblical historical record of the journey. ◇

|

The Biblical Chronologist is written and edited by Gerald E. Aardsma, a Ph.D. scientist (nuclear physics) with special background in radioisotopic dating methods such as radiocarbon. The Biblical Chronologist has a fourfold purpose:

The Biblical Chronologist (ISSN 1081-762X) is published by: Aardsma Research & Publishing Copyright © 2024 by Aardsma Research & Publishing. Scripture quotations taken from the (NASB®) New American Standard Bible®, Copyright© 1960, 1971, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. All rights reserved. www.Lockman.org } |

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, "The Route of the Exodus," The Biblical Chronologist 2.1 (January/February 1996): 1–9. www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, "The Route of the Exodus, Part II: The Encampment at Etham," The Biblical Chronologist 13.1 (February 7, 2023): 1–5. www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, "The Route of the Exodus, Part VI: The Location of Marah," The Biblical Chronologist 13.5 (June 13, 2023): 1–6. www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, "The Route of the Exodus, Part VII: The Location of Mount Hor," The Biblical Chronologist 13.7 (September 8, 2023): 1–10. www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ www.biblicalchronologist.org/search/advanced_search. php?epq=30+miles+per+day&q=&oq=&eq=&btn= Search+The+Biblical+Chronologist+Web+Site