| |

| Volume 14, Number 14 | August 27, 2024 |

My purpose this issue is to tell a long-hidden, true story from ancient history. It is the story of the acquisition of Israel's southern sector.

While the elements of this story are present within the biblical historical narrative of the Exodus, they appear to have been previously misunderstood, prohibiting their proper synthesis.

To get this story right, it is necessary first to get one's biblical chronology right.[1] One must be sufficiently informed to know that the traditional dates of the Exodus and the Conquest posited by scholars such as Bishop Ussher (died 1656 A.D.) are severely wrong. They are foreshortened by 1000 years, thereby prohibiting proper alignment of sacred and secular histories touching on these events.[2] The proper date of the Exodus is roughly 2450 B.C., and the proper date of the Conquest is roughly 2410 B.C.

The true story of Israel's southern sector demands for its telling a foundation of right biblical chronology because it is necessary first to get one's biblical geography of the route of the Exodus right to be able to tell it, and getting the biblical geography right can begin only once one knows the proper date of the Exodus.[3]

There was never any master plan by Moses to include a southern sector in the territories claimed by the newly-formed nation of Israel. His sights appear to have been fixed pretty much on Canaan. The inclusion of territory far to the south of Canaan—Israel's southern sector—came about because of unexpected opposition to the new nation from an unanticipated quarter. We must credit the inclusion of its southern sector to God, who sees the future and turns even evil designs to the betterment of those who love Him.

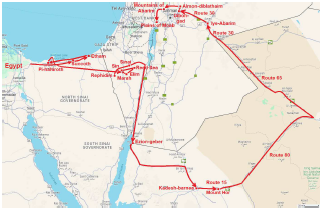

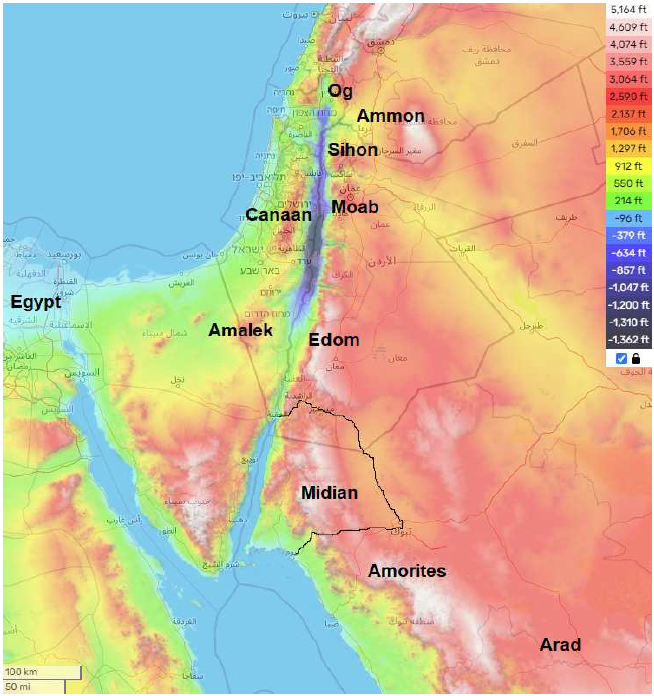

Much happened while Israel was camped along the Jordan River in the plains of Moab opposite Jericho. This was the final encampment of the Exodus (Figure 1). From there, they would eventually cross over the Jordan River and begin the Eviction/Conquest of Canaan with the well-known defeat and destruction of the city Jericho. But they seem to have been in no hurry. The biblical historical record of their stay at the Plains of Moab encampment is extensive. It unfolds beginning with Numbers 22, when the Israelites arrived there, continues for the remaining 15 chapters of Numbers and throughout the 34 chapters of Deuteronomy, and does not end until Joshua chapter 3, when they finally cross the Jordan into Canaan.

|

All of these chapters center around the wrapping up of Moses' 40-year leadership of the newly-formed nation. Moses was 120 years old when the nation arrived at the Plains of Moab encampment. He was at the end of the life span normal to individuals of his generation. We may picture Moses, at 120 years of age, in much the same physical condition due to the disease of modern human aging as people appear at 75 years of age today.

Most of the individuals whom Moses was leading would not have been of his generation, and they would have had much shorter life spans, similar to humans today. A program of infanticide against male Hebrew babies born in Egypt had been instituted shortly before Moses' birth by Pharaoh Phiops II (also known as Pepi II), the ruler of Egypt. Because of this, there would have been a dearth of male population in Moses' age group. Additionally, within a decade or two following Moses' birth, the oceans had finally exhausted their store of dissolved pre-Flood methylphosphine gas, bringing to an end natural production of the anti-aging vitamins methylphosphonic acid (MePA) and methylphosphinic acid (MePiA) in Earth's atmosphere.[4] This final depletion had been sudden, causing the life spans of all individuals born subsequently to drop to roughly 75 years, as it is today. Thus, the majority of the individuals whom Moses led to freedom would have had 75-year life spans.

Moses, at 120 years of age, would climb Mount Pisgah at God's command and die there in judgment of his failure long ago to follow God's instruction to speak to the rock to provide water at Kadesh-barnea. Moses' brother, Aaron, had died in a similar way and for the same reason atop Mount Hor (Numbers 20:24–28a), at the age of 123 years, six months previously,[5] following their departure from Kadesh-barnea (Figure 1).

Both Moses and Aaron had, as a part of God's judgment, been forbidden to enter Canaan. Thus, the nation could not cross the Jordan until Moses was dead and leadership had passed to Joshua. The historical narrative of the book of Deuteronomy ends with the death of Moses. The historical narrative of the following book of Joshua commences with Joshua in charge of the nation.

There was, unfortunately, no peace—no golden years, or even any golden months—for Moses at the Plains of Moab encampment. Moses' leadership of the nation of Israel along the route of the Exodus had been peppered with trials, and the Plains of Moab encampment offered more of the same. Such, all too often, seems to be the plight of godly leadership.

The final drama of Moses' leadership career began when Balak, king of Moab, began seeking a way to rid himself of what he believed to be the menace of the Israelites to Moab.

Balak's concern was completely unnecessary. The Israelites had been commanded by God not to harm or harass Moab. But Balak didn't seem to know this, and the Israelite nation was much on his mind, being encamped under his nose down on the plains of Moab, in the Jordan valley, at the feet of the mountains of Ar over and from which he reigned. The presence of the Israelites there was causing general anxiety among his people, evidently spurring him to take action.

Now Balak the son of Zippor saw all that Israel had done to the Amorites. So Moab was in great fear because of the people, for they were numerous; and Moab was in dread of the sons of Israel. (Numbers 22:2–3)

Balak's opening move was to dialogue about the problem with the elders of Midian.

And Moab said to the elders of Midian, "Now this horde will lick up all that is around us, as the ox licks up the grass of the field." (Numbers 22:3a)

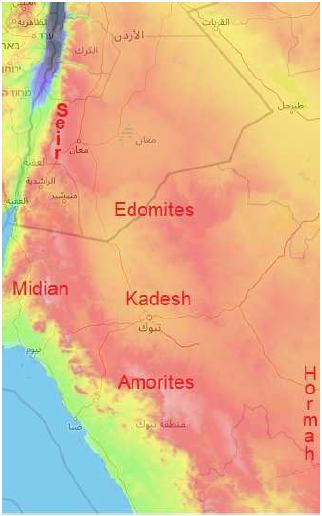

I think it is normal, when this verse is first encountered, to wonder what the Midianites have to do with Balak's (imagined) problem. The "elders of Midian" seem to appear out of nowhere at this point in the narrative. Why is Balak talking specifically to them about his problem with the Israelites? As I have previously suggested, Midian appears to have been located far to the south of Moab, west of Tabuk/Kadesh-barnea (Figure 2). (This location will be affirmed beyond reasonable doubt later in this article.) Why is Balak reaching out to them, way down there (Figure 3)? Why not reach out instead to Edom, his much nearer neighbor and distant kin just on his southern border, for example? Or to Ammon, his nearer kin just to the northeast of Moab, who had had, like Moab, a front-row seat during the defeat of Sihon and Og by the Israelites? Knowledge of the broader context of the overall biblical historical narrative provides answers to these questions.

|

|

Recall that Moses was married to a Midianite woman. Moses' father-in-law, Jethro, was "priest of Midian." Moses, after fleeing Egypt because he had murdered an Egyptian, lived in Midian for forty years, tending Jethro's sheep.

I have previously suggested that Tabuk/Kadesh-barnea was backwater wilderness of Midian and that Moses was able to camp there with the Israelites because of the diplomatic immunity which his marriage to his Midianite wife afforded him.

In this context, Balak's purpose for contacting the elders of Midian is clear. He was seeking inside information about how to deal with his (imaginary) problem of this newly emergent Israelite nation led by Moses.

Once this has been understood, his assertion to the elders of Midian, quoted above, takes on a new character. There is an implied accusation, like this:

And Moab said to the elders of Midian, "[You let these escaped slaves settle on your land and take root as a new nation. You have created a huge problem.] Now this horde will lick up all that is around us, as the ox licks up the grass of the field."

Before proceeding, notice that the Midianites involved in this interaction with Balak would have been at least a generation removed from Jethro, and that Jethro would likely have been long dead at this point.

This younger generation of Midianites had the option of refusing to act against Moses, their relative. But they chose instead to join Moab as an ally against Moses and the Israelites. It is this hostile alliance which is the root cause of Israel ending up with a southern sector to the south of Canaan.

It seems probable that Kadesh-barnea itself provided the motivation for this younger generation of Midianites to act against Moses and the Israelites. When the Israelites had settled there some 38 years previously, it had been a dry, barren wilderness. It was called "the wilderness of Zin." According to Strong's Concordance, "Zin" comes from a Hebrew root meaning "to prick." It thus appears that the Israelites had settled prickly desert. This would not refer to cacti, which are native only to the Americas, but rather to thorny desert brush native to that part of the world. The Israelites had turned this undesirable, backwater, prickly scrub desert into a city while they had lived there. Tabuk/Kadesh-barnea is today, in the middle of otherwise more or less barren desert, a vibrant, thriving city, surrounded by many acres of green agricultural fields all watered by wells from the underground reservoir of water which was first discovered and exploited by Moses. Cities represented a form of wealth back then just as they do today. By the time the Israelites left, Kadesh-barnea may be thought of as a shining jewel in the desert. The city's water rights alone must have been worth a fortune back at the time of Moses.

Moses and the Israelites had left Kadesh-barnea of their own volition, so there seems to be no doubt that they could have returned there if they had wished to. They had ownership rights in Midian to Kadesh-barnea. I suggest that the prospect of possessing this shining jewel motivated the younger generation of Midianites to side with Moab against the Israelites. All they had to do was to arrange for the downfall of Moses and destruction of the upstart nation of Israel, and Kadesh-barnea would fall undisputed into their hands.

The counsel given to Balak by the Midianites is not immediately spelled out in the narrative. It is necessary to piece it together from subsequent events. But it appears simply to have been this: call in Balaam, a prophet of God from the region of the Euphrates River to the north, to put a curse on the Israelites.

This strategy failed when God caused Balaam to bless the Israelites rather than curse them. But it appears that Balaam, some weeks later, went on to counsel the Moab/Midian alliance to entice the Israelites via feigned friendships and romantic relationships to turn their backs on God and begin to worship Moabite/Midianite gods so that God would become angry with the Israelites and turn His back on them. This counsel nearly succeeded, resulting in God sending a severe plague upon Israel.

The plague came as a wake-up call. Moses and the Israelites realized that they had been blindsided. They had been unaware of the evil strategy being worked out against them. There is no doubt that the machinations of Balaam and the Moabite/Midianite alliance had hit their target, wounding the young nation.

The final result, when Israel had repented in tears and turned back to God in heart and in deed, was 24,000 Israelites dead from the plague—and a war of retribution against Midian.

Then the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, "Be hostile to the Midianites and strike them; for they have been hostile to you with their tricks, …" (Numbers 25:16–18a)

The war with Midian resulted in the capture of the kingdom of Midian by the Israelites. It also resulted in the death of Balaam, who seems to have been present in Midian by that time. He, no doubt, had found increasing "ministry opportunity" with the Midian/Moab alliance.

Balaam's death at the hand of Israel's soldiers provides an explanation of how Balaam's story—of which no Israelite would have had firsthand knowledge—came to be included in the biblical historical record of the Exodus. His story could have been recorded by himself, just as Moses obviously recorded his own story and the story of the Exodus as it happened. The soldiers could have taken a record of his story, perhaps his journal, and turned it over to Moses.

But the important final result, for the present study, is that Midian's territory (Figure 3), including Tabuk/Kadesh-barnea, would thus have become territory of Israel, explaining how Israel came to have its southern sector.

This explanation, implicit in the narrative, is affirmed by the subsequent narrative. It is only when all of the Balak/Balaam-induced trouble had ended and Midian been defeated that Israel's southern sector appears in the narrative. It appears in Moses' specification of the boundaries of the new nation of Israel, appended to the long-anticipated territory of Canaan, when Moses' remaining days on earth must have been precious few.

Then the Lord spoke to Moses saying, "Command the sons of Israel and say to them, 'When you enter the land of Canaan, this is the land that shall fall to you as an inheritance, even the land of Canaan according to its borders. Your southern sector shall extend from the wilderness of Zin along the side of Edom, and your southern border shall extend from the end of the Salt Sea eastward. Then your border shall turn direction from the south to the ascent of Akrabbim, and continue to Zin, and its termination shall be to the south of Kadesh-barnea…' " (Numbers 34:1–4a)

I have previously shown this southern border in detail, including the ascent of Akrabbim.[6] It is the southern border of Midian, shown in Figure 3.

Secular history affirms the existence of Israel's southern sector in this location. From the wikipedia.org article on the Hejaz, under the heading "Prehistoric and ancient times," we find:[7]

According to Al-Masudi [who lived roughly 896–956 A.D.] the northern part of Hejaz was a dependency of ancient Israel, and according to Butrus al-Bustani [1819–1883 A.D.] the Jews in Hejaz established a sovereign state. The German orientalist Ferdinand Wüstenfeld [1808–1899 A.D.] believed that the Jews established a state in northern Hejaz.The northern part of Hejaz is the area east of the Red Sea's Gulf of Aqaba, including Tabuk. That is, it coincides with the area shown in Figure 3 as Midian.

Israel's southern sector was the territory of the former kingdom of Midian, won in a war of retribution with Midian. ◇

The Biblical Chronologist is written and edited by Gerald E. Aardsma, a Ph.D. scientist (nuclear physics) with special background in radioisotopic dating methods such as radiocarbon. The Biblical Chronologist has a fourfold purpose:

The Biblical Chronologist (ISSN 1081-762X) is published by: Aardsma Research & Publishing Copyright © 2024 by Aardsma Research & Publishing. Scripture quotations taken from the (NASB®) New American Standard Bible®, Copyright© 1960, 1971, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. All rights reserved. www.Lockman.org } |

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, A New Approach to the Chronology of Biblical History from Abraham to Samuel, 2nd ed. (Loda, IL: Aardsma Research and Publishing, 1995). www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, The Exodus Happened 2450 B.C. (Loda, IL: Aardsma Research and Publishing, 2008). www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, "Yeroham—The True Mt. Sinai?" The Biblical Chronologist 1.6 (November/December 1995): 1–8. www.BiblicalChronologist.org. Gerald E. Aardsma, "The Route of the Exodus," The Biblical Chronologist 2.1 (January/February 1996): 1–9. www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, Aging: Cause and Cure, 3rd ed. (Loda, IL: Aardsma Research and Publishing, 2023). www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ Numbers 33:38 records that Aaron died "in the fortieth year after the sons of Israel had come from the land of Egypt on the first day of the fifth month," and Deuteronomy 1:1-5 records that Moses expounded the law "in the Arabah… across the Jordan in the land of Moab" (i.e., from the Plains of Moab encampment) "in the fortieth year, on the first day of the eleventh month."

^ Gerald E. Aardsma, "The Location of the Ascent of Akrabbim," The Biblical Chronologist 14.7 (April 30, 2024): 1–5. www.BiblicalChronologist.org.

^ en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hejaz (accessed August 20, 2024).