|

|

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by:

Aardsma Research & Publishing

414 N Mulberry St

Loda, Illinois 60948-9651

www.BiblicalChronologist.org

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 778-0-9647665-6-3

| List of Figures | 5 | |

| Dedication | 7 | |

| Acknowledgements | 9 | |

| Preface | 11 | |

| 1 | Where to Find the Exodus | 15 |

| 2 | The Date of the Exodus | 19 |

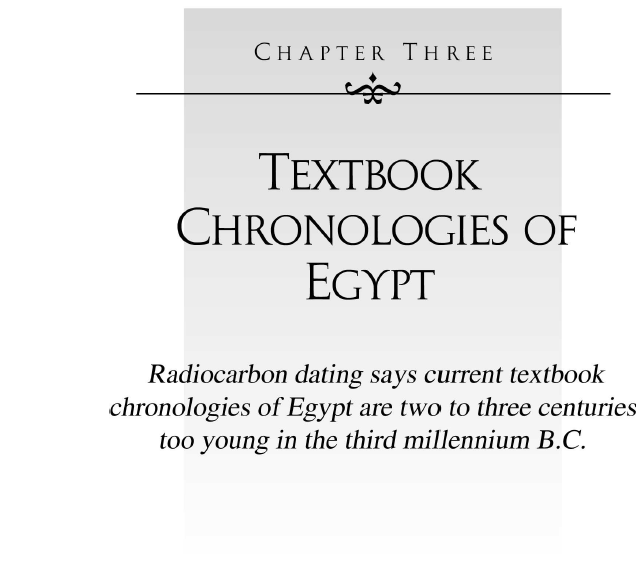

| 3 | Textbook Chronologies of Egypt | 27 |

| 4 | Synchronism #1: the Pharaoh of the Oppression | 31 |

| 5 | Synchronism #2: the Pharaoh of the Exodus | 39 |

| 6 | Synchronism #3: The Collapse of Egypt | 43 |

| 7 | Israelite Pottery Shards in the Sinai Desert | 47 |

| 8 | Israelite Encampments in the Sinai Desert | 55 |

| 9 | The Route of the Exodus | 61 |

| 10 | Objection #1: "The Way of the Land of the Philistines" | 71 |

| 11 | Objection #2: Horses and Chariots in Egypt | 77 |

| 12 | The Exodus Happened 2450 B.C. | 83 |

| Index | 90 | |

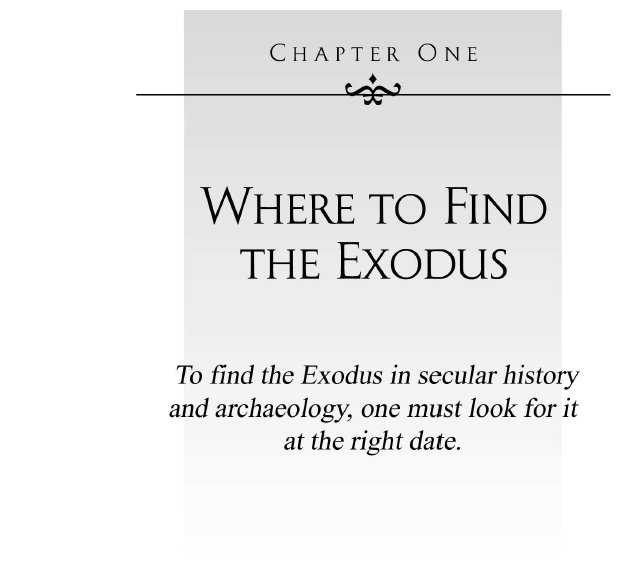

| 1.1 | Where to find the Exodus. | 17 |

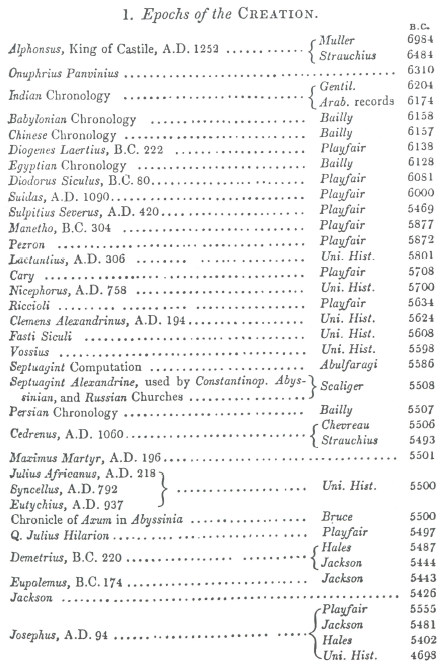

| 2.1 | One page of Hales' list of Creation dates. | 21 |

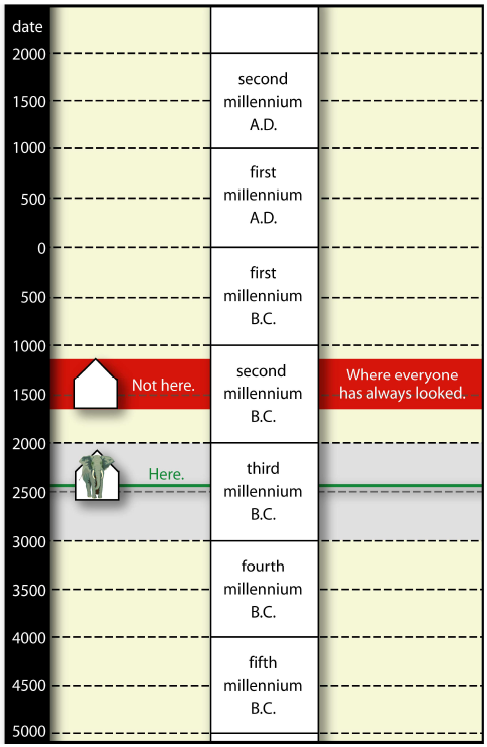

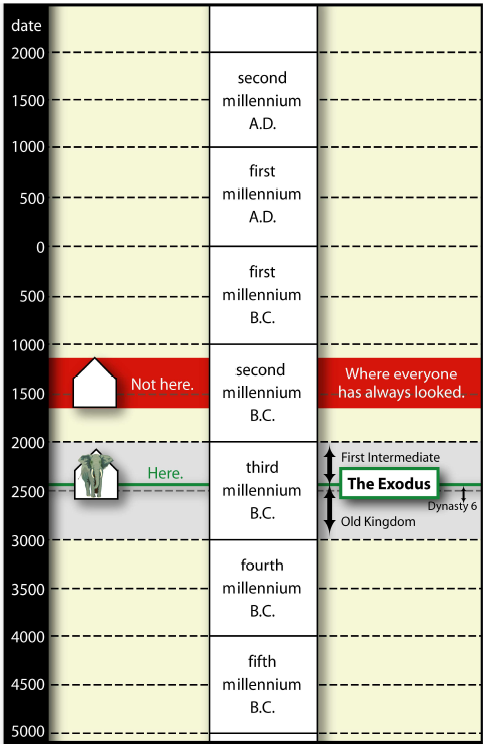

| 2.2 | Modern Biblical Chronology dates the Exodus to the middle of the third millennium B.C., not the second millennium B.C. where it has always previously been saught. | 25 |

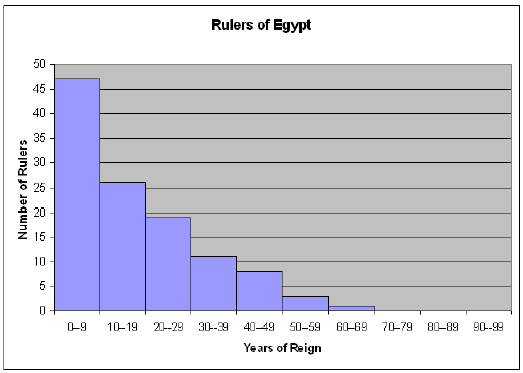

| 4.1 | Graph of 115 ancient rulers of Egypt. | 33 |

| 6.1 | The Exodus took place at the boundary of Egypt's Old Kingdom (which it terminated) and Egypt's First Intermediate period (which it caused). | 46 |

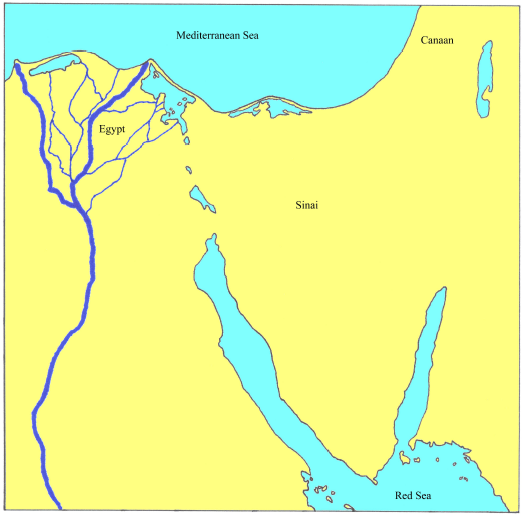

| 7.1 | The Sinai desert separates Egypt and Canaan. | 49 |

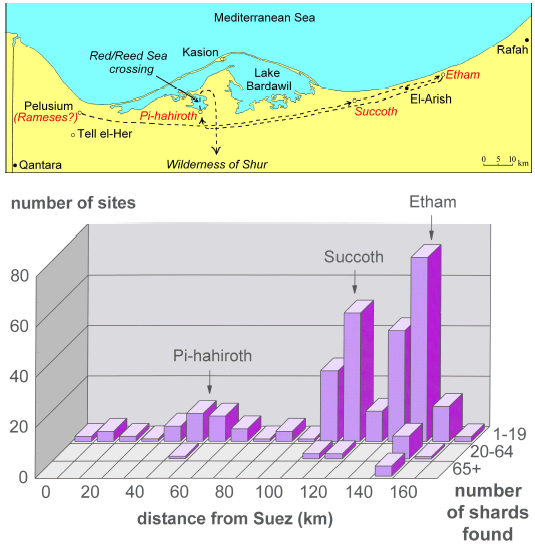

| 9.1 | TOP: Map of the North Sinai peninsula showing the route of the Exodus. BOTTOM: Distribution of sites by quantity of pottery shards found and distance from Suez. | 63 |

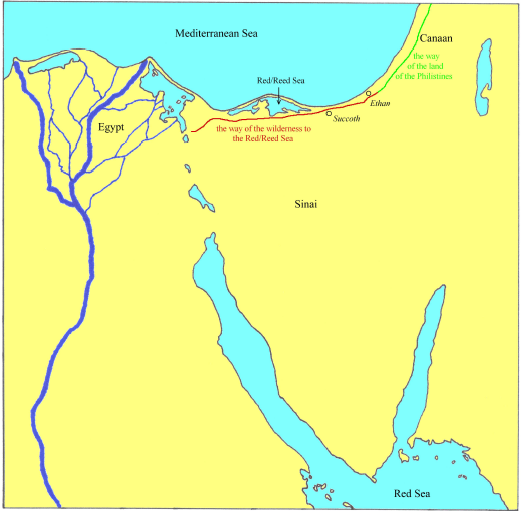

| 10.1 | Proposed identification of roads mentioned in Exodus 13:17--18. | 73 |

| 12.1 | A sample of the ubiquitous pottery shards found littering the plain before Mount Yeroham/Sinai. | 87 |

| 12.2 | The Exodus happened 2450 B.C. | 89 |

To my Proverbs 31 wife,

Helen,

with eternal love.

My heartfelt appreciation goes out to the following individuals who assisted in the production of this book:

Melissa Baccarella, Tom Godfrey, Steve & Jennifer Hall, and David & Hannah Rush read a first draft and provided critical feedback and comments.

Steve & Jennifer Hall provided graphic design and artwork, including the cover design. They also assisted with chapter titles and with some of the illustrations.

My wife, Helen, compiled the index and facilitated numerous details. She was frequently assisted by my youngest daughter Rachel.

The title of this book can be read with two different emphases: "The Exodus Happened 2450 B.C." or "The Exodus Happened 2450 B.C." My main purpose in writing this book rests with the first of these two emphases.

As with anything having to do with real history, this book is unavoidably dependent upon chronology. But it is not a book about chronology. It is a book about the Exodus—a book announcing that the Exodus has, at long last, been found in the history of Egypt and the archaeology of the Sinai peninsula, and explaining why it had never previously been found.

I will need to discuss two chronology items in the early chapters of this book, to show how to get the Biblical Chronology date of the Exodus right (chapter 2), and to show why one needs to synchronize biblical and secular chronologies of Egypt (chapter 3). But I will do so only briefly, as is suitable to my purpose, trusting you to make use of the references given in the footnotes to dig deeper should these chronology items be of larger interest to you.

The nature of this book is an announcement of something new, not a rehash of traditional viewpoints. It is written from a conservative Christian perspective, but categorically rejects all previous theories of the Exodus, whether liberal or conservative. It assumes the historical integrity of the Bible, and shows that sacred and secular data bearing on the Exodus harmonize without difficulty when this assumption is made, providing one has their Biblical Chronology date of the Exodus right.

In saying that the nature of this book is an announcement of something new, I do not mean to imply that all it contains is for the first time here presented. In actual fact, the breakthrough in the field of Biblical Chronology upon which this work is based (see chapter 2) was made and published over fifteen years ago, and a great deal of time and effort have been spent researching and communicating the implications of that breakthrough since that time. As a result, much of the material presented in this book has appeared elsewhere previously, especially in The Biblical Chronologist. Thus, while the nature of this book is an announcement of something new, this announcement has not been rushed to press in the present volume. It comes to you only after years of research, testing, contemplation, and discussion.

My years of experience with the biblical chronological breakthrough upon which this work is based have convinced me that it is valid in every way. This results both from its success in test after test which I have subjected it to, where it might easily and repeatedly have been falsified, and from the inability of others to show it invalid. But my long experience with this chronological breakthrough poses a bit of a communications difficulty for me, since it is not shared by most of my readers.

Imagine a colony of people who have grown up, all their lives, in space, far from any planet. Imagine they have no science education, and know nothing of gravity, either from theory or from experience. In their space environment, devoid of gravity, water floats around them in spheres of various sizes. Your task is to communicate to these people the fact that on Earth, where you come from, water invariably falls to the floor and remains plastered there. You may be sure they will find this fact difficult to believe—indeed they will probably judge it to be somewhat perverse, against nature and against common sense. They will find your 'simple' explanation of gravity and its effects to be unnecessarily contorted and obscure. And there is a good chance they will think you brash and arrogant if you state in simple honesty what you know from your experience to be true.

I have tried very hard to make this book a simple, logical, and honest presentation of factual information. If anything about it should strike you as brash or arrogant, please accept my apology, and put it down to my being a better scientist than politician.

Gerald E. Aardsma

September 19, 2008

Loda, IL

The entire Exodus story as recounted in the Bible probably never occurred.

–The New York Times, March 9, 2002.[1]

In actual fact, the Exodus did occur. And, I might add, if objective archaeological evidence counts for anything, it occurred in just the way the Bible says it did.

The quote above, from The New York Times, speaks for much of the scholarly, academic world today. It also speaks for a rapidly growing segment of their (misinformed) lay disciples. This Exodus-is-fiction group believes "the entire Exodus story as recounted in the Bible probably never occurred" because they think modern archaeology has proven this. They appear to disdain conservative Christians, we who cling tenaciously to our Exodus-is-fact view in the face of what they feel is overwhelmingly contrary evidence.

In one sense their disdain is easily understood. People who hold religiously to the view that there is a live, full-grown elephant in the garage, when every zoo-keeper in the country has thoroughly investigated the garage and found it to be empty of elephants, hardly deserve to be applauded. And still less do certain members of this group deserve to be applauded when they declare the investigation inconclusive because an oil can on the windowsill has yet to be looked under.

But in another, more vital sense, the disdain of the Exodus-is-fiction group is seriously misplaced. For there is a live, full-grown elephant in the garage, perfectly plain for everybody to see if they will only look in the right garage! The elephant is not housed at 1450 BC Street, or anywhere else in the second millennium BC block where everybody has always looked for it. It is housed at 2450 BC Street (Figure 1.1).

|

To determine the date of the Exodus one must turn to the field of Biblical Chronology. The Bible itself provides no B.C./A.D. dates for the historical events it records. It does, however, frequently provide chronological information within its historical narrative. For example, it may tell us how long a king's reign lasted, or how old a father was at the birth of his son. Using such chronological information, together with extra-biblical chronological data, the B.C./A.D. dates for biblical historical events, such as the Exodus, may be computed. This is the business of the discipline of Biblical Chronology.

Unfortunately, the discipline of Biblical Chronology is not infallible. Indeed, the history of this discipline shows that it is, if anything, rather error prone.

I enjoy looking through old books on Biblical Chronology. One published back in 1830 has a table listing dates of Creation computed by various Christian and non-Christian scholars known to its author, Reverend William Hales, D.D., back at that time (Figure 2.1). The table fills three pages. Following the table Hales summarizes as follows:[2]

Here are upwards of 120 different opinions, and the list might be swelled to 300; as we are told by Kennedy, in his Chronology, p. 350. This specimen, however, is abundantly sufficient to show the disgraceful discordance of chronologers, even in this prime era: the extremes differing from each other, not by years, nor by centuries, but even by chiliads [millenia]; the first exceeding the last no less than 3268 years!

|

The "disgraceful discordance of chronologers" which Hales here notes is hardly "disgraceful" in my opinion. It merely reflects the fact that the problem of building an accurate chronology of the distant past, whether secular or sacred, is hardly a trivial one.

In constructing a chronology of biblical history, the chronologist must deal with numerous uncertainties. For example, interpretive issues may arise over biblical chronological information. A well-known instance of this sort of uncertainty arises in connection with the genealogical lists found in Genesis 5 and 11. Should "begot" always be interpreted as meaning a direct father-son relationship, or might it signify a grandfather-grandson relationship in some instances?

The biblical chronologist must also deal with uncertainties arising out of issues of textual preservation. This may seem strange to some, for it is well known that the Bible is remarkably well preserved relative to all other ancient literature. In fact, the Bible is so well preserved that for nearly all practical purposes one may treat the modern copy of the Bible they hold in their hands as if it were equivalent to reading the original text of Scripture written multiple thousands of years ago. Unfortunately for the biblical chronologist, biblical numbers appear to be the biggest exception to this rule.

Difficulties in the preservation of biblical numbers are most easily exposed by different numbers appearing in parallel passages of the Bible. For example, 2 Kings 24:8 says (NASB), "Jehoiachin was eighteen years old when he became king…", while 2 Chronicles 36:9 says (NASB), "Jehoiachin was eight years old when he became king…".

Difficulties in the preservation of a biblical number may also be exposed by different numbers appearing in different ancient manuscripts of the Bible. For example, the ancient Hebrew (Masoretic) text says that Lamech lived 595 years after he fathered Noah (Genesis 5:30), while the ancient Greek (Septuagint) text says Lamech lived 565 years after he fathered Noah.

Much more difficult to detect are instances in which the original biblical number has been lost from all known ancient manuscripts of the Bible. 1 Samuel 13:1 is an example in this category.[3] According to Green's interlinear Hebrew and English Bible, the Hebrew text literally reads:[4]

A son of a year (was) Saul when he became king and two years he reigned over Israel.That is, the text literally says that Saul was a one year old baby when he became king, and that his reign lasted only two years.

We know this is not correct from the Old Testament's historical narrative of the reign of Saul. Saul was at least a young man when he was made king, and his reign had to last much longer than just two years. However, there appears to be no doubt that this verse was originally intended to convey two important quantitative pieces of information to the reader: Saul's age when he became king, and the length of his reign. Taking all things into consideration, modern conservative scholarship is led to the conclusion that some numbers must have been accidentally dropped out of the biblical text at some remote time in the past, accidentally shortening both Saul's age when he became king and the length of his reign. Conservative Bible scholar Gleason Archer has written regarding the first missing number in this verse, for example:[5]

Unfortunately textual criticism does not help us, for both the LXX [Septuagint] and the other versions have no numeral here. Apparently the correct number fell out so early in the history of the transmission of this particular text that it was already lost before the third century b.c.

Textual preservation problems are relatively rare even for biblical numbers. But these relatively rare problems can have large consequences for biblical chronology. As a result, the biblical chronologist is not allowed the luxury of simply taking numbers from the present text of the Bible at face value. He must, in every way possible, check the biblical numbers he uses in building his chronology of biblical history.

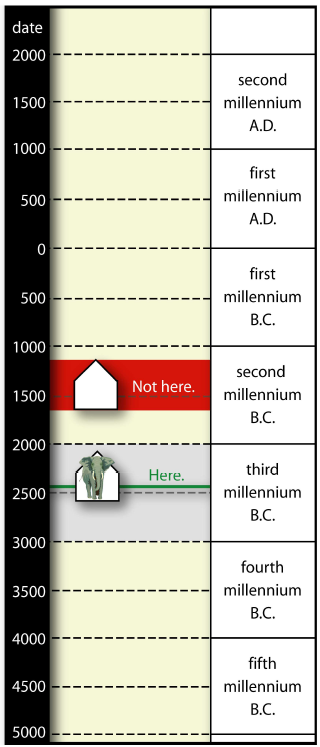

To compute the date of the Exodus it is necessary to use a biblical number found in 1 Kings 6:1. This verse reads (NASB):

Now it came about in the four hundred and eightieth year after the sons of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon's reign over Israel, …

This says that 480 years elapsed between the Exodus and the fourth year of Solomon's reign.

As it turns out, this number presents the biblical chronologist with an immediate difficulty. Specifically, the history which we are given in the Bible for the period of time from the Exodus to the time of Solomon is far too long to fit in a mere 480 years.

This is easily seen by adding up the well-known 40 years of wilderness wandering, 410 years of alternating periods of oppression and deliverance recorded in the book of Judges, 40 years for the career of Eli, 40 years for the reign of Saul, and 40 years for the reign of David. This already totals 570 years, though it does not include the time during which Joshua led Israel, nor the career of Samuel, and these two, while not specified biblically, probably total close to 80 years. They must certainly total to something greater than 30 years, which yields a total minimum sum for this interval of 600 years.

Thus, the biblical stipulation of 480 years from the Exodus to Solomon given in 1 Kings 6:1 conflicts with the greater than 600 year total for this same time period which can be calculated from chronological data given elsewhere in the Bible.

Traditionally, biblical chronologists have uniformly chosen to side with the "480 years" of 1 Kings 6:1. They have assumed that the chronological data given in Judges must refer to overlapping rather than consecutive time periods.

This, as it turns out, is the wrong choice. I will show the right way to solve this biblical chronological conflict in a moment. For now the important thing to notice is that this wrong choice is the whole reason why everyone has always looked for the Exodus at the wrong date.

Traditional Biblical Chronology, treating the "480 years" of 1 Kings 6:1 as definitive, dates the Exodus to approximately 1450 B.C. It does so by adding 480 years to 970 B.C., which is the (approximate) Biblical Chronology date of Solomon's ascension to the throne. (A more detailed calculation yields 1447±12 B.C. for the traditional Exodus date.[6])

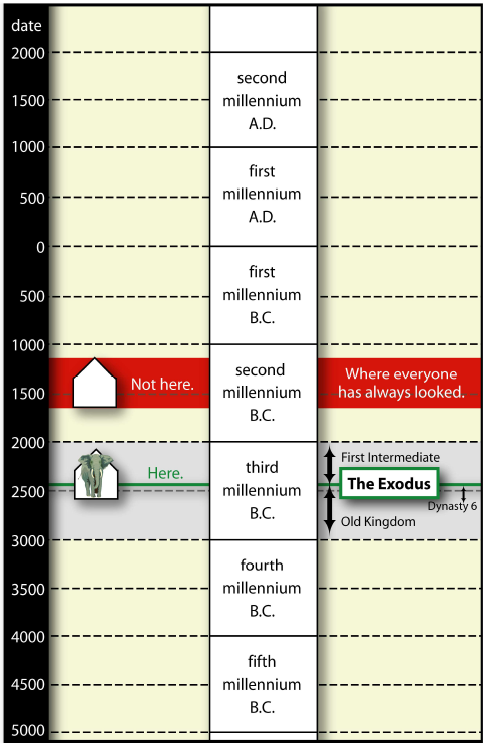

This places the Exodus in the middle of the second millennium B.C. Some scholars have ventured to stray from this biblically computed date by several hundred years for one reason or another, but all have felt constrained to remain within reasonable reach of the middle of the second millennium B.C. because they felt Biblical Chronology demanded this. (See Figure 2.2.)

|

But the discipline of Biblical Chronology demands no such thing. It allows chronologists to side with the "480 years" of 1 Kings 6:1 if they wish, but it does not demand that they do so. It presents an alternative—that the greater than 600 year total which one gets by taking the biblical chronological numbers in Judges at face value may be correct, and that there may be something wrong with the "480 years" of 1 Kings 6:1.

As it turns out, this second possibility is the correct choice.[7] The "480 years" of 1 Kings 6:1 has suffered the same sort of (rare) problem we saw above in relation to 1 Samuel 13:1. Just as in that case a numeral had been dropped out of the text so that Saul's reign should not be "2 years" as all extant manuscripts presently read, but rather "_2 years", where the blank represents a lost numeral, in the same way, in the present case, a numeral has been dropped out of all extant manuscripts of 1 Kings 6:1 so that the time between Solomon and the Exodus should not be "480 years" but rather "_480 years".[8]

It turns out that the correct number for 1 Kings 6:1 is 1,480 years rather than just 480 years.[9] This means that the correct date for the Exodus is approximately 2450 B.C., not approximately 1450 B.C. And this is why, despite exhaustive searching, the Exodus has never been found by historians or archaeologists in the second millennium B.C., and why it will never be found there. It does not belong to the second millennium B.C. It belongs to the third millennium B.C.

For this reason it is an error to conclude that, since an exhaustive, decades-long search of the second millennium B.C. has failed to turn up any evidence of the Exodus, therefore "the entire Exodus story as recounted in the Bible probably never occurred". In actual fact, when one looks in the middle of the third millennium B.C., evidence of the Exodus is overwhelmingly found.

It would be very nice if we could take a current textbook on ancient Egypt from the library shelves and learn, for example, who the pharaoh of the Exodus was by simply looking up who was pharaoh at the new Biblical Chronology date for the Exodus (i.e., 2450 B.C.). Alas, life is not so easy. Just as construction of an accurate biblical chronology is not a trivial exercise, so also the construction of an accurate chronology of ancient Egypt is not a trivial exercise. Today the chronology of ancient Egypt, back in the middle of the third millennium B.C. where we are interested, is uncertain by several centuries.

This fact is shown most clearly by modern radiocarbon dates on Egyptian monuments.[10] These argue for an extension of the third millennium B.C. chronology of Egypt by two to three centuries relative to what can be found in most current textbooks. This means, for example, that if the textbook assigns a date of 2450 B.C. to some pharoah's ascent to the throne of Egypt, the true date of that pharaoh's ascension, according to radiocarbon, is probably closer to 2700 B.C.

This finding is strongly supported by a series of radiocarbon dates from Jericho, reported by Bruins and van der Plicht:[11]

In conclusion, the collective 14C evidence of the Early Bronze Age from Jericho and other sites in the southern Levant as well as from Egypt for the Predynastic period and Dynasties 1-6 strongly challenges the current archaeo-historical time framework for these cultural and political periods. Most 14C dates overwhelmingly show that these periods are significantly older than currently accepted.

Because of this uncertainty in the third millennium B.C. chronology of Egypt, it is necessary to search for one or more synchronisms between the biblical narrative of the Exodus and the third millennium B.C. secular history of Egypt to align the biblical and secular histories of the Exodus.

As it turns out there is a very clear triple synchronism which makes this alignment task relatively easy. The next three chapters present this triple synchronism, one synchronism per chapter.

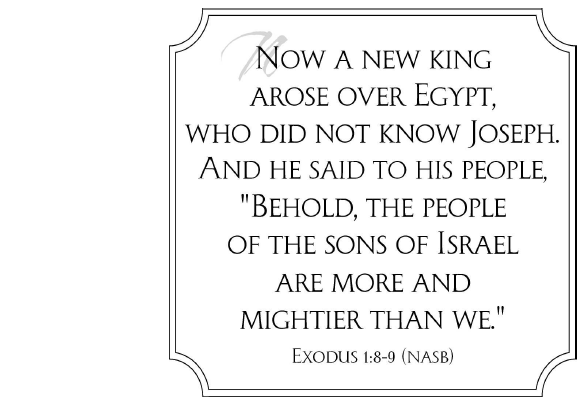

The history of the Exodus is told in the Bible in the book of Exodus. Trouble began for the Israelites, all of whom were then living in Egypt, when a new pharaoh came to the throne, one "who did not know Joseph".[12] We call this pharaoh the "pharaoh of the Oppression". He enslaved the Israelites and tried to limit their population by a program of infanticide.[13] Moses was born under his rule—and was nearly a victim of his infanticide program, but was rescued and raised by this pharaoh's daughter.[14] As a grown man, Moses fled from this pharaoh after murdering an Egyptian, and did not return to Egypt until this pharaoh had died.[15]

Moses was 80 years old by the time he returned to Egypt.[16] Thus the Hebrews suffered under the rule of the pharaoh of the Oppression for the better part of a century. The book of Exodus remembers his long-awaited death with the words, "Now it came to pass in the course of those many days that the king of Egypt died".[17]

The important point in all of this for the present purpose is the observation that the pharaoh of the Oppression ruled for more than 80 years. Eighty years is an unusually long reign. In fact, it is so unusual it provides a means of identifying the pharaoh of the Oppression in secular Egyptian history with near certainty.

Figure 4.1 shows graphically the probability of a pharaoh reigning for such a long time. To construct this graph, I have used chronological data for rulers of Egypt presented in the appendix of Nicolas Grimal's A History of Ancient Egypt.[18] (Nicolas Grimal is Professor of Egyptology at the University of Paris, Sorbonne.) Because of chronological difficulties of one sort or another, not all rulers of Egypt listed in Grimal's appendix were listed together with the chronological data needed to compute their length of reign. But 115 rulers did have the necessary data, and the graph in Figure 4.1 is from those 115 rulers.

|

The graph makes it clear that a reign of greater than 80 years is very rare. It shows that most rulers lasted less than 10 years—47 of the 115 rulers are in this category. Only 1 of the 115 rulers reigned for more than 60 years. This was Ramesses II, who ruled for 67 years in the second millennium B.C., 1279–1212 B.C. according to Grimal's chronology. None (zero) of these 115 rulers of Egypt reigned for more than 80 years.

There is no pharaoh of Egypt who reigned for 80 or more years anywhere in the second millennium B.C. But there is a ruler of Egypt who lived in the third millennium B.C. who is reported to have ruled more than 80 years. This ruler was Phiops II (also called Pepi II). The ancient Egyptian historian Manetho reported that he came to the throne at age six, and died in his one hundredth year, having reigned for 94 years.[19]

Because this is the only pharaoh of Egypt recorded by secular history to have reigned more than eighty years, because a reign of more than eighty years is very rare, and because he reigned in the third millennium B.C. where modern Biblical Chronology expects this long reign, we may conclude with near certainty at this stage that Phiops II was the pharaoh of the Oppression. This conclusion is confirmed beyond all reasonable doubt by two further synchronisms, shown in the next two chapters.

Before moving on to these two synchronisms, however, I need to address two potential objections to the present synchronism. The first potential objection is that the biblical narrative does not explicitly say that there was just one pharaoh for the entire duration of the Oppression, making the long reign of Phiops II irrelevant. The second potential objection is that Phiops II would be unable to have a daughter old enough to satisfy the biblical narrative of the discovery and adoption of the infant Moses by the pharaoh's daughter.

The biblical narrative nowhere explicitly says that just one pharaoh ruled Egypt for Moses' first eighty years. However, it is the natural sense of the narrative that this was the case, and this is all we require for the present purpose of aligning sacred and secular chronologies in the third millennium B.C.

That the narrative, when read in its natural sense, involves just one pharaoh of the Oppression, has been understood by ordinary Christians for a very long time. Look, for example, at the following passage by Alexander Whyte, a remarkable student of the Bible and preacher of more than a century ago. Speaking of the pharaoh of the Oppression he says [italics are mine, for emphasis]:[20]

Come on, let us deal wisely with them, said the ill-read and ignorant sovereign who sat on the throne of Egypt at the time when the children of Israel were fast becoming more and mightier than their masters. Come on, was his insane edict, let us deal wisely with them, lest they multiply and it come to pass that, when there falleth out any war, they join themselves to our enemies and fight against us. Therefore, they did set taskmasters over them to afflict them with their burdens. But the more they afflicted them the more they multiplied and grew. Till in a policy of despair this demented king charged all his people, saying, Every son of the Hebrews that is born ye shall cast into the river, and every daughter ye shall save alive. This is all that remains on the statute-book of Egypt to testify to the statesmanship of that king of Egypt who had never heard of Joseph the son of Jacob, the servant of Potiphar, and the counsellor and deliverer of the kingdom. That was the statute-book, and that was the sword and the sceptre, that this Pharaoh handed down to his son who succeeded him, and who was that new Pharaoh whom God raised up to show in him His power, and that through him His name might be declared throughout all the earth. A Pharaoh, says Philo, whose soul from his cradle had been filled full of the arrogance of his ancestors. And indeed, he was no sooner sat down on his throne, we no sooner begin to hear his royal voice, than he at once exhibits all the ignorance and all the arrogance of his ancestors in the answer he gives to Moses and Aaron: Who is the Lord that I should obey Him? I know not the Lord, neither will I let Israel go. Get you to your burdens. It is because you are idle that you say, Let us go and do sacrifice to the Lord. Go, therefore, for there shall no straw be given you, and yet you shall deliver your tale of bricks! The father had not known Joseph, and the son knew neither Joseph, nor Moses, nor Aaron, nor God.

It is perfectly clear that Whyte, with no ax to grind, found just two pharaohs in the Exodus narrative: the (one) pharaoh of the Oppression, and his son, whom Moses and Aaron confronted when Moses was eighty years old.

This natural reading is not possible, of course, for a second millennium B.C. Exodus, once the secular history of Egypt is known, as it is today. As we have seen, there is no pharaoh who ruled for eighty or more years in the second millennium B.C. Thus, the absence of any explicit biblical statement to the effect that only one pharaoh ruled Egypt for the first eighty years of Moses' life has seemed for a long time to provide the only way out for those wishing to defend the historicity of the Bible in the face of current knowledge of the history of Egypt. But we do not need to employ this device in the case of a third millennium B.C. Exodus. Rather, we find that the natural reading of the biblical narrative—despite the inherent improbability of a reign lasting more than eighty years—is fully realized in the reign of Phiops II. And it becomes apparent that this is no mere coincidence—that the natural reading is fully vindicated—when this fact is coupled with the additional two synchronisms which follow it, which we will consider in the next two chapters.

The second potential objection is that Phiops II would be unable to have a daughter old enough to satisfy the requirements of the biblical narrative of the discovery and adoption of baby Moses.

If Phiops II was one hundred years old when he died, and Moses was eighty years old when he returned to Egypt soon after the death of Phiops II, as we have seen above, then Phiops II would have been twenty years old when Moses was born. (In this and the following calculations there is an uncertainty of about a year due to the ages involved being rounded to the nearest whole year.) If we take thirteen as the youngest age at which a human male can father a child, then Phiops II could not have had a daughter any older than seven (plus or minus one) years at the time of her discovery of the infant Moses.

This is quite young, to be sure, but it is not too young. Reading through the short biblical narrative of the discovery and adoption of Moses by the daughter of Pharaoh (Exodus 2:1–10) reveals nothing which is fatal to the idea that the daughter of Pharaoh was only seven years old at the time. Her ability to give commands and be obeyed (Exodus 2:5, 8&9) is adequately explained by her status as princess and does not require that she be a young woman. Her pity for the crying baby also does not require a mature womanhood; in fact, it is all the more probable in a young girl. And a young girl would be far less likely to be deterred from acting in accord with her female instincts, by, for example, considerations of the potential impact on her own reputation of sheltering a slave child, or considerations of the practicalities involved in adopting a baby and raising it.

Finally, notice that Moses' sister, who was watching him, was probably just six or seven years of age herself. In natural breastfeeding societies (i.e., all societies prior to the relatively recent advent of bottle feeding and commercial baby foods) children are naturally spaced about three years apart because they are breastfed for the first several years of life and breastfeeding acts as a natural contraceptive. Thus we are not surprised when the Bible tells us that Aaron was three years older than Moses (Exodus 7:7). We are not told Miriam's age, but she was probably just three years older than Aaron. This would make her six years old at the birth of Moses. In any event, Miriam was almost certainly just a young girl, and the willingness of the princess to interact with Miriam on her own terms (Exodus 2:7&8) is more easily understood if the princess was also a young girl.

The idea of Phiops II having a child at age thirteen may seem a bit shocking, but it is not difficult to find adequate motivation for such a young age of fatherhood in the normal pressures of a hereditary monarchy to produce an heir to the throne.

It is certainly the case that the biblical narrative regarding the pharaoh of the Oppression and his daughter places highly unusual constraints upon the life of the pharaoh of the Oppression when taken at face value. To have reigned for more than eighty years, as a natural reading of the Bible requires, and to have had a daughter old enough to do the things the Bible describes at such an early point in his reign, requires a monarch who lived and reigned at least into his very late nineties. I know of only one monarch, in all of recorded human history who meets these requirements, and that monarch is the pharaoh Phiops II. Against all odds, this monarch rules over no other country than Egypt, and at no other time than in the middle of the third millennium B.C. (more on the date below)—that is, just where and when the biblical narrative of the Exodus at the new Biblical Chronology date for the Exodus demands. I will not hurry all of this to the conclusion that the Exodus happened 2450 B.C. (even should you feel that the writing is on the wall). That conclusion belongs to the final chapter of this book. For now I merely observe that consideration of Phiops II for the present purpose of aligning secular and sacred chronologies in the third millennium B.C. is in every way completely valid.

When Moses returned to Egypt he stood before a new pharaoh. We call this pharaoh "the pharaoh of the Exodus".

We do not mean by this label to exempt this pharaoh from participation in the Oppression, for the biblical record is clear that he was every bit as oppressive of the Israelites as the previous pharaoh had been. But his oppressive role was brief, for God had had enough. And it is mainly the new pharaoh's role in negotiations with God over letting the Israelites leave Egypt for which we remember him. So we call him the pharaoh of the Exodus.

Moses, with his brother Aaron as spokesman, did not demand of the pharaoh of the Exodus that he let the Israelites go free from their slavery. He requested only that they be granted a three-day religious holiday which the Lord was demanding of them.[21] But the pharaoh of the Exodus said that he neither knew the Lord nor had any intention of obeying Him.[22]

And then followed a sequence of power politics. The pharaoh of the Exodus tightened the screws by increasing the Israelites' labor, and beating them up when they failed to attain his impossible demands. God responded by sending a series of nationwide disasters on Egypt, generally following a warning together with opportunity to avoid the disaster by complying with God's demand for a three-day holiday.[23]

The pharaoh of the Exodus responded with belligerence, demands for compromise, mistreatment of God's messengers (Moses and Aaron), and repeated lying—until God had had more than enough, and struck the Egyptians with the death of their first-born.[24]

The pharaoh of the Exodus then commanded the Israelites to leave—immediately.[25]

The Israelites left, but a few days later the pharaoh of the Exodus decided that he had made a mistake. He mustered his army and took it into the desert to bring the Israelites back.[26]

He thought he had trapped them against a body of salt water. But then the Israelites made a miraculous escape through the body of water when God sent an all-night wind to dry a path through the middle of it.[27]

The pharaoh of the Exodus went with his army in pursuit of the Israelites along the dry path through the body of water. But the waters returned to their normal state, and the pharaoh of the Exodus and the entire Egyptian army were drowned—"not even one of them remained" Exodus 14:28 tells us, while Psalm 136:15 doubly assures us that, contrary to Hollywood portrayals, the pharaoh drowned too: "But He overthrew Pharaoh and his army in the Red Sea..." (NASB).

The important point in all of this for the present purpose is the observation that the pharaoh of the Exodus—the successor to Phiops II—should have a very brief reign.

The successor to Phiops II was Merenre Antyemsaf II. Secular history does not record the manner of his death, but it does record that his reign lasted one year only.

Phiops II is followed in the Abydos List by a Merenre who was also called Antyemsaf and must not be confused with the earlier and more important Merenre. The name is broken off in the Turin Canon, where the length of reign is given as one year.[28]

Thus the biblical signature of an extraordinarily long reign followed by a very short reign is fully satisfied in the Phiops II – Merenre Antyemsaf II combination of secular Egyptian history in the third millennium B.C.

It seems somewhat incredible that scholars familiar with the known history of Egypt and the biblical record of the Exodus should ever have labored to fit the Exodus into a second millennium B.C. framework. The biblical account of the Exodus demands the collapse of Egypt following the Exodus, and there simply is no collapse of Egypt in the second millennium B.C.

Would the United States of America survive as a nation were it to experience today the nationwide calamities which God brought upon Egypt in his dealings with Merenre Antyemsaf II in the third millennium B.C.?

Imagine if, within a few weeks time, the United States of America were to suffer severe pollution of all its drinking and irrigation water, uncontrollable infestations of frogs and insects in its homes and in its food reserves, an outbreak of boils on all its people so severe that they are unable even to stand up, death of all its livestock, destruction of all its forests and standing crops by hail, complete denuding of the ground by locusts so that no agricultural crop survives, three days of total darkness, and finally death of a high percentage of the population—for all of this happened to Egypt immediately prior to the Exodus. Pharaoh's counselors, still only part way through this initial series of calamities, said to him, "Do you not realize that Egypt is destroyed?"[29]

But these nationwide calamities were not the end of the trauma Egypt suffered at the time of the Exodus. When the Israelites left they took with them the wealth of the land—silver, gold, and clothing.[30] The modern American equivalent would mean loss of much of the money supply so that few have a dollar, either in their pocket or in their bank account.

In addition, the pharaoh and his army were completely destroyed. In modern terms this would mean death of the President and of all America's soldiers and loss of all military equipment.

And finally, when the Israelites walked away they deprived Egypt of her slave labor force. This is roughly equivalent to the sudden loss of America's industrial machinery.

The analogy of modern America to ancient Egypt is not perfect, of course. The global ties and rapid global communication and transport which exist today give America a potential resilience not paralleled in the case of ancient Egypt. But the analogy seems adequate to show the utter ruin of Egypt which the Exodus must have caused.

The second millennium B.C. history of Egypt displays nothing like this. In fact, roughly the opposite of utter ruin is what one finds at the traditional date (1450 B.C.) for the Exodus. This date places the Exodus near the beginning of an extended period of uninterrupted strength and prosperity for Egypt. This period of prosperity was founded upon the military might of the warrior-pharaoh Tuthmosis III, who established a vast Egyptian empire by conquering everything worthwhile within striking distance of Egypt—including all of Palestine. This prosperity persisted and grew, coming eventually to full bloom about a century later under Amenophis III. I doubt whether a more unlikely setting for the Exodus can be found in the entire history of Egypt.

In sharp contrast, utter ruin of Egypt is found immediately following the reign of the pharaoh of the Exodus, Merenre Antyemsaf II. The period of prosperity scholars call the "Old Kingdom" comes to an abrupt end, and there begins a centuries-long interval of chaos which scholars call the "First Intermediate" period.

It was the collapse of the whole society, and Egypt itself had become a world in turmoil…[31]

Thus a triple synchronism—an extraordinarily long reign, followed by a very short reign, followed by the collapse of Egyptian civilization—is found between the biblical record of the Exodus and the secular history of Egypt in the third millennium B.C., allowing us to align these two chronologies. This triple synchronism unequivocally places the Exodus at the end of the reign of Merenre Antyemsaf II. This corresponds (Figure 6.1) to the end of the sixth dynasty, the end of the Old Kingdom period in Egypt, and the beginning of Egypt's First Intermediate period. This provides precise alignment of the biblical Exodus narrative relative to the secular history and archaeology of Egypt.

|

In absolute terms, Grimal's chronology[32] places the date for all of this near 2200 B.C. But radiocarbon sides with modern Biblical Chronology in placing the date near 2450 B.C.[33]

The Bible tells us that over 600,000 men—not counting women and children—came out of Egypt under the leadership of Moses at the time of the Exodus. It seems there can be no mistake about this number, for it is given in Exodus 12:37, repeated in Exodus 38:26, Numbers 1:46, 2:32, 11:21, and 26:51, and broken down into its component parts by genealogical descent in Numbers chapter 2 and again in Numbers chapter 26.

It seems reasonable to assume that there were roughly the same number of women as there were men, and we shall probably err on the low side if we assume that there was one child for every woman. Thus, it can be estimated that there were probably in excess of one million eight hundred thousand people who participated in the Exodus. Let us call it an even two million.

A rough check of this estimate can be quickly calculated using rate of population growth. The Bible records that seventy persons accompanied Jacob at the start of the Israelites' stay in Egypt.[34] It also records that the duration of the Israelites' stay in Egypt was 430 years.[35] Two million people from seventy people after 430 years computes to an average population growth rate for the Israelites of about 2.4% per year. Wikipedia reports that the population growth rate for the world peaked at 2.2% per year in 1963.[36] We know that the rate of population growth for the Israelites in Egypt was large. Concern over it was, in fact, the whole basis of the Oppression.[37] So 2.4% per year for the Israelites in Egypt seems reasonable, corroborating the estimate that roughly two million people participated in the Exodus.

Now I have a very simple, and—I think—obvious proposal to make: it is impossible for two million people to cross the desert between Egypt and Canaan (Figure 7.1) and leave no material trace of their presence. I venture to suggest that, were a similar size multitude of families to be led on a camping expedition from Egypt to Israel today, the trail of discarded soda cans alone would be sufficient to discern their passage five thousand years hence.

|

I do not mean this comparison to be entirely facetious. The Israelites did not bring along any soda cans, of course, but they would necessarily have brought along numerous pottery vessels. For example, Exodus 12:34 tells us they brought along kneading bowls: "So the people took their dough before it was leavened, with their kneading bowls bound up in the clothes on their shoulders" (NASB). Of the hundreds of thousands of such vessels which must have been brought along during the Exodus, a small fraction would inevitably have been broken one way or the other each day. The fragments of such broken pottery—the shards—would then simply have been discarded, leaving an extremely durable and distinct record of the Israelites' presence.

The discarded shards would leave a "durable" record because fired pottery shards are essentially indestructible when left to the elements. They do not rust or decay, and as they have no intrinsic economic or utilitarian value they are likely to be left indefinitely lying where they were initially discarded.

The discarded shards would leave a "distinct" record because archaeology has shown unequivocally that the composition, design, and decoration of pottery vessels changes from one culture to another and from one time period to another. Pottery shards can therefore be used with a very high degree of precision to identify when and by whom the pottery vessels from which they came were originally made.

Discovery of any pottery shards due to the Israelites at the time of the Exodus has proven to be another impossible task for a second millennium B.C. Exodus. The case is quite different, once again, for a third millennium, 2450 B.C. Exodus.

To show this, let me begin by specifying four identifying characteristics—four signatures—which must be satisfied by shards from pottery vessels used by the Israelites at the time of the Exodus. The purpose of these four signatures is to allow shards of pottery vessels actually used by the Israelites at the time of the Exodus to be unambiguously identified. Let us call shards displaying these four signatures "Exodus pottery".

To get from Egypt to Canaan on foot, the Israelites had to cross the Sinai desert (Figure 7.1). The distance was too great to complete this journey in a single day. The Bible tells us that the Israelites set up temporary camps along the way. Thus, the first signature of Exodus pottery is that it will be found in ancient campsites in the Sinai desert.

The Israelites comprised a distinct culture residing in the northeastern delta region of Egypt during their enslavement. They can be expected to have made and utilized their own distinctive pottery while in Egypt, and to have continued doing so on their way to Canaan, and to have gone on doing so once they had conquered Canaan and settled there.

When they left Egypt, the pottery they carried with them would be expected to be predominantly of their own manufacture, but not exclusively so. They had been living in Egypt and among the Egyptians. Thus there is every reason to suppose they would initially have possessed some fraction of Egyptian pottery as well. Thus the second signature of Exodus pottery is that its shards should be predominantly of a characteristic non-Egyptian pottery style, but (at least initially) with an admixture of characteristic contemporary Egyptian pottery.

The third signature of Exodus pottery is that the Egyptian shards must necessarily be of a style which was in use in Egypt at the time of the Exodus. We have, in the previous chapter, pinpointed this time to the end of the Old Kingdom and beginning of the First Intermediate period.

The fourth and final signature of Exodus pottery is that the non-Egyptian shards must necessarily be of a style which subsequently came to be dominant in Canaan, due to the Israelites' eventual conquest and occupation of Canaan. The time period corresponding to the Israelites eventual conquest and occupation of Canaan (which is not recognized as Israelite, but rather believed to be Canaanite by archaeologists erroneously assuming a second millennium B.C. Exodus date) is variously called Middle Bronze Age I, Intermediate Bronze Age, or Early Bronze Age IV, depending on the preference of the archaeologist. Thus the non-Egyptian shards must date to the Middle Bronze Age I / Intermediate Bronze Age / Early Bronze Age IV period in Palestine.

We have, then, four signatures of Exodus pottery. The first specifies where Exodus pottery is to be found—in the Sinai desert between Egypt and modern Israel. The second specifies what Exodus pottery will be like—predominantly non-Egyptian with an admixture of contemporary Egyptian shards. The third and fourth specify when Exodus pottery will date to—end of the Old Kingdom/beginning of the First Intermediate Period for the Egyptian shards, and Middle Bronze Age I / Intermediate Bronze Age / Early Bronze Age IV for the non-Egyptian (Israelite) shards. These four signatures are sufficiently time and space specific to unambiguously identify pottery actually used by the Israelites at the time of the Exodus.

One of the things which archaeologists do is to explore large areas by walking or riding across the ground, cataloging the location and type of pottery shards they find lying about on the surface. These sorts of studies are called surface surveys. They help the archaeologists to know where people were living at various periods in the past.

Significant surface surveys were conducted in the Sinai peninsula in the sixties and seventies. Fortunately—for our purpose of finding the route of the Exodus, at least—the Sinai peninsula has, since very ancient times, not been regarded as a very nice place to live, so the catalog of pottery shard finds for this region is relatively small and uncomplicated.[38]

The most important surface survey for our present discussion was conducted by Eliezer D. Oren from 1972 to 1982 on behalf of the Ben Gurion University. Oren's research resulted in the following discovery, succinctly summarized by archaeologist Ram Gophna:[39]

… Egyptian pottery has been identified among the finds of the North Sinai survey conducted by the Ben Gurion University in the seventies (led by E. D. Oren). The Egyptian shards were found together with pottery typical of the Intermediate Bronze Age in Israel at 45 campsites of the period discovered during the survey.

This quote immediately displays three of our four Exodus pottery signatures. It informs us of the discovery of:

pottery from Sinai desert campsites,

mixed non-Egyptian (Israelite) and contemporary Egyptian shards, and

an Intermediate Bronze Age date for the non-Egyptian (Israelite) pottery component.

The remaining signature regards the time period for the Egyptian pottery. Oren and Yekutieli wrote regarding the Egyptian shards that they were "typical of Upper and Middle Egypt sites of the 4th and 6th dynasties and of the beginning of the First Intermediate Period."[40] Oren and Yekutieli went on to discuss the pottery of these campsites in the larger context of similar pottery from Egypt and Israel and narrowed the date of the campsites they had discovered "to the beginning of the Middle Bronze I period, i.e., to the period of time that in Egypt coincides with the end of the sixth dynasty and the beginning of the First Intermediate Period …"[41] This fulfills the fourth signature of Exodus pottery precisely.

Thus we may conclude that shards of pottery vessels actually used by the Israelites of the Exodus have been found in North Sinai. These shards bear witness to the passage of the Israelites from Egypt to Canaan 2450 B.C.

What were the early encampments of the Israelites like? Did the Israelites pitch their tents in neat "city block" fashion, as is sometimes depicted in Sunday school illustrations?

In point of fact, the biblical record suggests the Israelite camps prior to Mount Sinai were unstructured. While the Israelites were at Mount Sinai, God specified a unique arrangement of the camps which, we must suppose, was only subsequently adhered to.[42] Thus it seems most probable that the initial Exodus encampments were unstructured.

Imagine the first day's journey from Rameses to Succoth. Picture two million people hurrying along an ancient road away from Egypt, carrying what earthly possessions they were able and accompanied by their flocks. Obviously, such a large group would be spread out over a considerable distance along the road. I calculate that two million people walking 50 abreast with 1 yard between rows of 50 would form a column nearly 23 miles long. After walking from probably before sunrise until probably after sunset, they stop at last and set up camp. Their camp must also have stretched several dozen miles along the road. Not surprisingly, Exodus pottery reveals archaeological sites which harmonize readily with just such a picture.

In the previous chapter I introduced a paper by Eliezer Oren and Yuval Yekutieli[43] describing what we now recognize to be Exodus pottery. Oren and Yekutieli did not find Exodus pottery in single, enormous, individual campsites; rather they found discrete clusters of many sites of various sizes along an ancient roadway. These clusters were not arranged in "city block" fashion. Rather, their arrangement was unstructured.

I do not mean to suggest that these clusters were found to be devoid of all organization. In fact, they were found to exhibit just the kind of natural organization one would expect of the tribal, pastoral Israelites. Oren and Yekutieli describe what they found as "clusters of sites with large settlement units at their center and smaller settlements at their margins".[44] Their description seems fully compatible with the identification of the large sites as the central hub of activity for one or more of the Israelite tribes. Around the large sites were medium size sites which, they suggest, represent the living quarters of families. Around the periphery of these were small sites which they identify as the campsites of shepherds—those who watched the flocks.

The size of these clusters is certainly suitable to the number of people involved in the Exodus. The archaeological data suggest that discrete encampments of the whole population were spread out along the road for a distance of roughly twenty miles, and that they covered an area in excess of four square miles.

All of this is what we would expect of the Israelites at the time of the Exodus from what we know of them from the Bible.

Because of the mistaken universal expectation that the Exodus should be found in the second millennium B.C., Oren and Yekutieli were totally unaware that these third millennium B.C. sites might correspond in any way to the biblical Exodus event. Indeed, they proffer the idea that pastoral tribesmen of uncertain origin lived at these sites for a period of time, and suggest that these tribesmen penetrated into Egypt at the end of the Old Kingdom, helping to bring about its collapse by the burdensome addition of their numbers to a supposedly already "overpopulated and drought stricken" delta region. They did not connect these sites with the Exodus at all.

Notice that Oren and Yekutieli's interpretation of these sites is, in effect, an Exodus in reverse. This is not surprising. It is impossible for Oren and Yekutieli to tell which came first, the campsites or the collapse of the Old Kingdom. The two are simply too close in time to be resolved by any physical dating method. It is as if Oren and Yekutieli's archaeology has provided them with disconnected frames, or slides, from a motion picture of the past. These slides can be used to tell many different stories about the past, depending upon the order in which one chooses to project them onto the screen. Oren and Yekutieli have projected them in one of the many possible erroneous sequences. To learn the proper chronological sequencing of these slides, one must turn to the Bible.

Oren and Yekutieli's lack of awareness that these sites are due to the Exodus gives their report both an immunity from the charge of biased observation, and a resultant cogency for the present purpose of showing that these sites are indeed due to the Israelites of the Exodus. Consider two additional observations they made regarding these sites, where Exodus pottery has been found.

First, Oren and Yekutieli report: "In some of the sites were found clusters of stones arranged in piles. Their purpose is not clear, but they were probably not burial monuments."[45] These, I suggest, should be recognized as altars.

The method of construction of altars was codified at Mount Sinai, only a short while after the Israelites had vacated these North Sinai sites. There they were commanded to build altars either from earth or from uncut stones.[46] As the construction of altars for the worship of Jehovah goes back through the centuries of Israelite history prior to the Exodus, ultimately to Abraham,[47] the instructions regarding construction materials given at Mount Sinai should be regarded almost certainly as mere legislative codification of already established practice. Thus, while altars of earth would long ago have weathered away,[48] there is every reason to expect piles of stones to remain today from stone altars constructed by the Israelites of the Exodus.

Second, the Bible records that the Israelites lived in booths (i.e., temporary shelters made of readily available vegetation, such as branches, twigs, and reeds) after they left Egypt:

You shall live in booths for seven days; all the native-born in Israel shall live in booths, so that your generations may know that I had the sons of Israel live in booths when I brought them out from the land of Egypt.[49]Oren and Yekutieli report: "it looks as if the inhabitants lived in booths…"[50]

While no encampments of the Israelites of the Exodus have ever been found anywhere in the second millennium B.C. despite considerable effort by archaeologists over many decades, when we look in the middle of the third millennium B.C. suitable encampments are readily found in the Sinai desert as expected.

Scholars have puzzled over the route of the Exodus for quite a few centuries. Today one can find a selection of theories regarding it in most standard Bible encyclopedias. Scholars' inability to determine the true route of the Exodus was understandable a generation ago—it is inexcusable today.

A generation ago, scholars had only the biblical text and the geography of the Sinai peninsula to go on. This was simply too little information to uniquely determine the actual route the Israelites took from Egypt to Palestine. In the last several decades, however, the situation has changed entirely. The biblical and geographical data have now been strongly supplemented with data from the field of Biblical Archaeology. In particular, extensive surface surveys have been carried out in the Sinai peninsula. The nature of the resultant archaeological data is such that the encampments made by the Israelites at the time of the Exodus cannot help but be exposed by them.

Unfortunately, modern conservative Bible scholars have largely eschewed the biblical archaeological data bearing on this question. This approach to the problem has been dictated by necessity, not preference. It has been a necessity because the biblical chronological framework which these scholars have assumed—the second millennium B.C. Exodus framework—misdates the Exodus by a full thousand years. This gross chronological error prohibits any meaningful alignment of any of the biblical narrative prior to the time of Eli and Samuel with any significant biblical archaeology datum, as we have repeatedly seen in foregoing chapters. As a result, scholars have been unable to make any sense of the archaeological data, and they have generally opted simply to ignore them.

Since the problem which gave rise to this erroneous biblical chronology has now been discovered and mended, it is no longer necessary to labor under this handicap. Working within a third millennium B.C. Exodus framework, the route of the Exodus is quickly revealed when the data of archaeology are brought to bear on the question. Figure 9.1 shows the result, which I will discuss in detail below. First, however, a brief overview, focussed on the biblical description of the route of the Exodus using the map shown in Figure 9.1, seems appropriate.

|

The Exodus was launched from Rameses.[51] This may refer to a region rather than a city. This is where the Israelites had settled on coming to Egypt: "So Joseph settled his father and his brothers, and gave them a possession in the land of Egypt, in the best of the land, in the land of Rameses, as Pharaoh had ordered" (Genesis 47:11, NASB).

Their first stop after leaving Egypt was Succoth.[52] We are not told how long they stayed there before moving on to Etham. Succoth is located in the desert. Lack of water would rapidly have become a problem. This suggests that their stay there lasted probably just a few days.

Etham is located on the edge of the desert[53] in a region where potable water as well as natural food sources are more readily available. They may have stayed in Etham significantly longer than they had in Succoth. The greater numbers of pottery shards found there (bottom chart of Figure 9.1) suggests this was the case.

In Etham they were on the verge of Canaan. But God did not want the people to enter Canaan that way. They were not yet ready for war,[54] and God was not yet finished with Egypt. So He instructed the Israelites to turn back from Etham and camp in front of the sea at Pi-hahiroth. God was setting a trap for Merenre Antyemsaf II and his army.[55]

Merenre Antyemsaf II read the Israelites' turning back to mean that they were wandering about aimlessly in the desert. They were now camped back on his doorstep. He decided to drive them back to slavery in Egypt.[56] The much smaller number of shards found at Pi-hahiroth (bottom chart of Figure 9.1) relative to the other two sites suggests that Merenre Antyemsaf II did not take long in coming to this decision.

He thought he had the Israelites trapped against the sea at Pi-hahiroth, which is about three miles wide and three miles across today. But God sent an all-night wind which drove the waters back and dried a path through the sea.[57] Merenre Antyemsaf II woke to find the Israelites' camp empty. He went after the Israelites along the path they had taken through the sea, but the waters returned to their normal state, drowning the entire Egyptian army.[58]

The Israelites, free of the Egyptian threat, took up their journey to Canaan through the Wilderness of Shur to the south.[59]

The archaeological data underlying the route shown in Figure 9.1 are the Israelite encampment sites discussed in the previous chapter. The basic data, once again due to Oren and Yekutieli,[60] are summarized graphically in the bottom of Figure 9.1. Three discrete clusters of sites along the ancient road connecting Egypt and Canaan are revealed by this graph. These three clusters, I suggest, correspond to the first three encampments of the Israelites: Succoth, Etham, and Pi-hahiroth.

Etham is the most easily identified of the three encampments because the Bible tells us the route of the Exodus doubled back from Etham.[61] Thus, it must be the cluster farthest from Egypt (i.e., farthest from Suez in Figure 9.1). This assignment also agrees with the biblical situation of Etham on the edge of the wilderness.[62] After discussing the near inability of the desert of North Sinai to support any permanent settlement, Oren and Yekutieli show that the location of their rightmost cluster of sites, which I have identified as Etham, is suitably situated on the edge of the modern-day desert as follows:[63]

Next to these unattractive conditions, there exist in the northeastern Sinai, between Rafah and El Arish, better ecological conditions that are conducive to permanent settlement and to a combination of a pastoral mode of life with rural agriculture.

Pi-hahiroth is also easily identified because the Bible tells us that it was located on the shore of a sea.[64] This sea must be capable of being partially dried by wind and crossed by two million people in a single night.[65] Figure 9.1 shows that this requirement is not met by either the Succoth or Etham clusters of sites, but that it is easily met by the left-most cluster. The site marked on the map as Pi-hahiroth is Oren and Yekutieli's site BEA34, which they describe as "one of the largest sites" they discovered.

The Bible locates Pi-hahiroth "opposite Baal-zephon" and says that it "faces Baal-zephon".[66] As with nearly all of these early sites, scholars are uncertain of the location of Baal-zephon. However, one candidate which has been suggested in the past is shown as Kasion in Figure 9.1. Kasion is located on a hill on the narrow natural earth dam which separates Lake Bardawil from the Mediterranean Sea. Site BEA34 appropriately "faces Baal-zephon" and can be said to be "opposite Baal-zephon" if Kasion is indeed Baal-zephon.

The Bible also locates Pi-hahiroth between Migdol and the sea.[67] Once again the archaeologists and historians are uncertain of the location of the Migdol referenced here. "Migdol" means tower and is usually considered to imply a fortified site. It would make sense, of course, for Egypt to maintain a border garrison in the vicinity of Pi-hahiroth. In fact, there is a second biblical Migdol at a very much later date, referred to in the books of Jeremiah and Ezekial, which scholars generally associate with Tell el-Her south of Pelusium. This much later Migdol seems unlikely to be the Migdol of interest in the present case, but it confirms that sites suitable to the name "Migdol" existed in antiquity on the northeastern border of Egypt in reasonable proximity of Pi-hahiroth.

This leaves the middle cluster of sites as Succoth.

Exodus 12:37–39 requires that Succoth be outside the boundaries of ancient Egypt. The location of Succoth shown in Figure 9.1 obviously meets this requirement.

The name Succoth means booths. The implication is that this name was given to the first encampment—which was characterized by booths, as we have already seen—by the Israelites themselves. This has as a further implication the possibility that the site was otherwise unnamed. In fact, the placement of Succoth shown in Figure 9.1 appears to be well removed from any other permanent feature (such as a town or village) of this period.

I have tentatively identified the extensive ancient ruins called Pelusium with the biblical Rameses in Figure 9.1. I have done this on the basis of a single consideration. I have assumed that the individual encampments were separated by a distance which could be traversed in a single day, unless the text explicitly states otherwise (as in Numbers 33:8, for example, where a three day journey is specified between two encampments). The distance between Pelusium and the point I have shown as Succoth is about sixty miles. This is already a very long distance for a single day's walk, yet Pelusium is the closest site to Succoth which seems a reasonable candidate for the biblical Rameses. As the assumption of a single day's journey between encampment sites is not mandated by the biblical text, the identification of Pelusium with Rameses is not certain. I put it forward only as what seems at this time to be a possibility.

I have been unable to locate any report of archaeological work at Pelusium which might confirm or deny this identification. The earliest levels appear to be below the present-day water table at this site, which possibly explains the lack of pertinent archaeological information.[68]

The body of water adjacent to Pi-hahiroth is called the "Red Sea" in Exodus 15:22 in the New American Standard Bible, with the marginal note, "Literally, Sea of Reeds". The Hebrew is yam-suph. Conservative scholar Kenneth A. Kitchen explains:[69]

The yam-suph would not be the Red Sea of today; … the Hebrew term corresponds to Egyptian tjuf, "papyrus," and should here be rendered "sea of reeds."

Lake Bardawil (Figure 9.1) appears to be a marshy saltwater lake. In the Rand McNally Bible Atlas, Emil G. Kraeling says regarding it:[70]

On certain portions of this lake there are big areas of rushes, so that the name "Sea of Reeds" would be an appropriate designation.

Kraeling goes on to say about Lake Bardawil:

The lake is forty-five miles long and thirteen miles wide. Major C. S. Jarvis, one-time governor of Sinai, describes it as an enormous clay pan about six to ten feet below the level of the Mediterranean Sea, and separated from the sea by a very narrow strip of sand, one to three hundred yards in width.Thus, the depth of Lake Bardawil appears to be about ideal—shallow enough to be partially dried by wind in a single night, yet deep enough to drown Pharaoh Merenre Antyemsaf II and his army, as the biblical narrative demands.

Finally the portion of Lake Bardawil north of Pi-hahiroth seems easily crossed by two million people in a single night. This sub-lake is presently just over three miles across. This distance can easily be covered in forty-five minutes by a person who is walking briskly. The real question, however, is whether two million people could funnel through the wind-dried path through this portion of the lake in time. The answer to this question depends upon how wide the wind-dried path was, which we are not told. However, to get a feel for the time needed for the Israelites to cross, first note that the sub-lake of Lake Bardawil north of Pi-hahiroth is some three miles wide. Assume that the middle third of this sub-lake was dry, making a one mile wide path. This leaves one mile wide strips of water on either side of the path to be "like a wall to them on their right hand and on their left".[71] If they walked at the rate of four miles per hour, and each person took up an area of six square feet, then I calculate it would take the group roughly fifty-two minutes to get across.

Conservative scholars, working within the traditional second millennium B.C. Exodus framework, have had a terrible time trying to map any convincing route for the Exodus. In standard reference works such as Bible handbooks or encyclopedias they generally present a selection of routes for the reader to choose from. This smorgasbord approach, of course, amounts to tacit admission that none of the proposed routes is very compelling.

Liberal scholars, also working within the traditional second millennium B.C. Exodus framework, deny the Exodus ever happened. They take the complete absence of archaeological evidence for any second millennium B.C. excursion of people across the Sinai desert from Egypt to Canaan as a proof of their position.

This all changes when we drop the false premise that the Exodus happened in the second millennium B.C., and begin to look for the Exodus in the third millennium B.C. where modern Biblical Chronology tells us it should be found. Available archaeological data then combine readily with the biblical account to yield one, and only one, route of the Exodus—the route shown in Figure 9.1.

The route of the Exodus which I have drawn in Figure 9.1 lies along the ancient road which connected Egypt and Canaan across North Sinai. Some may object that this route conflicts with Exodus 13:17–18 which says (NASB):

Now it came about when Pharaoh had let the people go, that God did not lead them by the way of the land of the Philistines, even though it was near; for God said, "Lest the people change their minds when they see war, and they return to Egypt." Hence God led the people around by the way of the wilderness to the Red Sea;…

The common approach to these verses equates "the way of the land of the Philistines" with the North Sinai road. As a result many scholars interpret these verses to mean that the Israelites did not use the North Sinai road at all during the Exodus. (Some even go so far as to say that God "forbade" the Israelites to use this road, though the text certainly says no such thing.)

But this equation appears to be in error. It appears that "the way of the land of the Philistines" should be applied not to the North Sinai road, but to the extension of the North Sinai road beyond Etham (Figure 10.1).

|

Notice, first of all, that it would be unnatural to call the North Sinai road "the way of the land of the Philistines". North Sinai was not part of the land of the Philistines. It seems more natural for "the way of the land of the Philistines" to be located in Philistia, not in the North Sinai desert.

Notice also that the reason given for not taking "the way of the land of the Philistines" is that the people were not yet ready for war. There would be no threat of war along the ancient North Sinai road. It ran through uninhabited desert. The threat of war would only arise if Israel passed beyond the desert into the fertile, inhabited region of Canaan, that is, if they went beyond Etham.

If I have not missed anything, "the way of the land of the Philistines" is only ever mentioned in the Bible in this one reference, and there appears to be no helpful ancient extra-biblical mention of it. Thus, in attempting to understand which road is being referred to we have only this single Bible reference to go on.

The proper identification of the road referred to in this single Bible reference depends critically upon the geographical context one assumes for these verses. If one assumes the people are still in Egypt, getting ready to leave, then when these verses say "the way of the land of the Philistines… was near" the North Sinai road seems to be the road which is being referenced.

But the geographical context of these verses is not Egypt. By the time the narrative gets to these Exodus 13:17–18 verses, the geographical context is Succoth. The people left Egypt back in Exodus 12:37, "Now the sons of Israel journeyed from Rameses to Succoth…" (NASB). And a few verses after the Exodus 13:17–18 passage in question, they leave Succoth and journey on to Etham: "Then they set out from Succoth and camped in Etham…" (Exodus 13:20; NASB). So the narrative places the Israelites in Succoth, not Egypt, when "the way of the land of the Philistines" is mentioned.

Once one accepts Succoth as the proper geographical context of these verses, all reason for equating "the way of the land of the Philistines" with the North Sinai road vanishes.

The North Sinai road, I suggest, is what the verses in question refer to as "the way of the wilderness to the Red Sea" (Figure 10.1). To see this, notice first of all that the "Red Sea" is, as discussed in the previous chapter, literally the "Sea of Reeds", and this Sea of Reeds is, according to the previous chapter, what modern maps show as Lake Bardawil. Thus Lake Bardawil is the "Red Sea" of the verses in question. And this immediately implies that "the way of the wilderness to the Red Sea" is the North Sinai road, which appropriately, whether viewed from Egypt or from Canaan, both runs through the wilderness and leads to the Red Sea / Sea of Reeds.

To take these verses as a declaration that the Israelites stayed off the North Sinai road is, I suggest, to misunderstand their purpose. I suggest their actual purpose is to explain why the Conquest of Canaan was not launched immediately from Succoth.

Such an explanation is surely necessary when we realize (as any ancient reader of these verses would have) that, having achieved Succoth, the Israelites were free of Egypt and on the threshold of Canaan. Why did they not immediately begin the Conquest from that point? Why would they move on from Succoth only to halt at Etham, on the edge of the wilderness? Why didn't they just keep going into Philistia using "the way of the land of the Philistines" which "was near" Succoth, and get on with the Conquest? The intent of Exodus 13:17–18 is not to make us believe that the Israelites never set foot on the ancient road linking Egypt and Canaan across the North Sinai desert at the time of the Exodus; rather, its intent is to answer these questions. The answer is given in verse 17: "Lest the people change their minds when they see war, and they return to Egypt" (NASB).

In this context, when verse 18 says, "Hence God led the people around by the way of the wilderness to the Red Sea", it does not mean that God led the people in a wide berth of Philistia, by a road in some entirely different direction, known as "the way of the wilderness to the Red Sea". Rather, it means that God led the people "around" (i.e., in a loop; from Succoth to Etham, then back around to Pi-hahiroth) on the road known as "the way of the wilderness to the Red Sea".

One might ask why God would do such a thing. Wouldn't God have led them as directly as possible along some safe route to Canaan?

The biblical narrative provides the answer to this question. It shows that God was not too concerned about getting Israel to Canaan as quickly and efficiently as possible at this point in their journey. It shows that it was the Egyptians, not the Israelites, who were the focus of God's plan during this portion of the narrative.

Exodus 14:1–4 is where we read that God told Moses to turn back from Etham. There we are told that this instruction was specifically given to cause Pharaoh to conclude that the Israelites were aimlessly wandering about so he would come out after them and try to drive them back to slavery in Egypt. Exodus 14:4 informs us that God's purpose in this plan was to teach the Egyptians that He, and not Pharaoh or any of their idols, was God.

"The way of the land of the Philistines" should not be equated with the North Sinai road. Rather, it should be equated with the extension of that road beyond Etham which runs through Philistia (Figure 10.1). The North Sinai road should be equated with "the way of the wilderness to the Red Sea".

God led the Israelites across the North Sinai desert, along "the way of the wilderness to the Red Sea", with "the way of the land of the Philistines" the next leg of the road beyond Etham. But His purpose was not that they should enter Canaan that way. His purpose was to teach the Egyptians that He was God. Thus He led the Israelites around in a loop on "the way of the wilderness to the Red Sea", doubling back at Etham. Only when His purpose had been accomplished with the Egyptians did the focus shift to preparing the Israelites to enter Canaan.

The claim seems widespread that the horse and chariot were introduced into Egypt by the Hyksos in the second millennium B.C. According to this claim, the biblical narrative of the Red/Reed Sea crossing—with pharaoh pursuing the Israelites through the sea with horses and chariots[72] — seems an embarrassing anachronism for a third millennium B.C. Exodus. Worse yet is the picture of Joseph riding in pharaoh's "second chariot"[73] some 430 years earlier still.

But this claim seems deficient in several ways.

First, it seems deficient in regard to basic logic. There is a general maxim which one must apply to archaeological evidence in all cases. This maxim is usually adhered to by competent archaeologists. The maxim is: "Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence".

This maxim becomes increasingly important as one moves back in time within the archaeological record, for at least two reasons:

chances of preservation of archaeological remains diminish as the elapsed time increases between creation of any object and the present, and

human populations diminish as one moves back in time, resulting in creation of fewer archaeological remains to begin with.

Second, the claim seems deficient in regard to presently available data for both horses and chariots.

I have done some (very limited) reading within the technical literature regarding horses in Egypt, and this reading suggests that the claim that horses were only introduced into Egypt by the Hyksos is on very shaky empirical ground at present.